By Mr C. Parsons

…a centre of power and movement will form itself, on which everything depends; and against this centre of gravity of the enemy, the concentrated blow of all forces must be directed.

―Carl von Clausewitz[1]

It is time to rethink the way we visualise military operations. The Clausewitzian concept of centre of gravity is no longer sufficient, even though it remains useful. Equilibrium theory provides new tools for the complexity of the twenty-first century security environment. In this regard, today’s globalised security environment has many similarities to the global economic system.

Centre of Gravity

According to Carl von Clausewitz the key to victory is attacking the enemy’s centre of gravity – the centre of all power and movement. The lesson of World War One is that massing forces against the centre of gravity spells attrition not victory. That said, centre of gravity analysis is useful for simplifying complicated (as opposed to complex) systems. Joe Strange and Colonel Richard Iron advanced a four step method that breaks a system into four parts: the centre of gravity is supported by critical capabilities that have critical requirements, which in turn are exposed to critical vulnerabilities.[2]

Strange and Iron’s recipe is scrumptious fodder for military academies the Western World over. Yet all too often what is plated up are logic leaps, linear thinking and a grail-like search for decisive victory in a world that does not offer it any longer. Logic leaps are the hackneyed result of cookie-cutter centres of gravity being used to drive analysis, rather than letting analysis lead understanding. Lines of operations, branches and sequels are all useful tools for coordinating effort and planning contingencies but they do nothing to explain second order effects, unintended consequences or tipping points. And, although noble sacrifice for bold decision helps justify the expenditure of blood and treasure, decisive victory is increasingly illusive in the complex cauldron of modern conflict. For example, the centre of gravity for violent idealist organisations is like the centre of a hollow sphere – there is nothing there; no capital to take, no army to defeat, only beliefs, and attacking beliefs just serves to magnify them.[3] In a networked world – stable equilibrium, not victory, is success.

Complexity

We need to remove our intellectual monocle – a fine eighteenth century Prussian monocle though it is – and use two new lenses, complexity and economics. In today’s security environment States are no longer the sole owners of power.[4] Money, information, pandemics, and transnational threats all transcend national borders in ways unforeseen by the lockstep nationalism of the Clausewitzian world.[5] The modern security environment is what scholar Scott Page describes as a complex adaptive system.[6]

Page defines the elements of a complex system as ‘agents,’ which are diverse, connected, interdependent and adaptive. [7] In a macroeconomic context, agents include governments, entrepreneurs, workers, consumers and even criminals who operate a black economy. They are connected in multiple different ways ranging from social media to international financial systems. This web of connections means that the behaviour of agents in one part of the system influence the behaviour and confidence of agent’s elsewhere in the system, thereby impacting market stability and causing the system to learn and adapt. In a security context, agents may be governments, violent extremists, private citizens and even environmental or biological factors. These agents are connected in many various ways including mass media, culture, ideology and geography. Agents influence each other and are therefore interdependent. For instance, an Islamic State terrorist can post an atrocity on YouTube, which convinces a lone wolf to randomly kill innocent citizens in an unrelated country, which in turn affects the travel plans of many other unrelated persons in many other countries. This in turn triggers a learning response from those within the system – and the system adapts.

Managing volatility is very important in complex adaptive systems. Page uses a scale of one to ten. One is stasis, nothing is going on: diversity is low, connectedness and interdependence are weak and there is little to no learning or adaptation.[8] Ten is chaos. Page calls three to seven the ‘interesting in-between’; there is a good flow of information, interaction and learning among diverse agents. At this level a complex system evolves and innovates without breaking down. However, as complex systems get bigger the relationship between risk and scale is exponential. As a result, small causes can trigger exceptional events, which change the whole system radically. Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls these ‘black swans’.[9]

Negative black swans can cause catastrophic collapse. One example is the contagion of the global financial crisis that was sparked by the collapse of Lehman Brothers Bank in 2008. Another example is the Arab Spring’s ongoing violent disorder, sparked by a single Tunisian street vendor setting himself on fire.

Preventing catastrophic collapse is our challenge. James Rickards, author of Currency Wars, proposes two means of doing so. Either reduce the scale of the system or, if that is not possible, prevent any one component from getting too large.[10] A third option would be to prevent destabilising pressures from converging to create a tipping point. Systemically today’s security environment has four fundamental pressures that need stabilisation: (1) inter-state competition seeks to ‘reorder’ the system, (2) violent extremists seek to ‘overthrow’ the system, (3) villains seek to ‘subvert’ the system to their advantage, and (4), natural forces have the potential to ‘overwhelm’ the system through disasters, pandemics and environmental change.

The bottom-line is that complex systems need to manage multiple ‘masses’ that are connected but not necessarily subordinate to centers of gravity. As a result, ‘Clausewitzian gravity attacks’ frequently lead to multiple unintended consequences and chaos. This is as true in economics as it is on the battlefield. For instance, many central banks have regarded inflation as the centre of gravity for economic stability. Yet a sharp increase in interest rates to reduce inflation can cascade into severe economic contraction. New Zealand experienced this in the 1980s and 1990s when two successive finance ministers waged an economic blitzkrieg dubbed ‘Rogernomics’ and ‘Ruthanasia.’[11] The New Zealand economy was relentlessly restructured and deregulated, the dollar was floated and money supply tightened. As a result interest rates climbed to a peak of 20.5%. Unemployment grew, wages were cut, industry fled overseas, poverty increased and foreign debt quadrupled.[12] There were many good results too, but a more measured restructure would have allowed the market to adapt without dangerous volatility.

Equilibrium

Success is the maintenance of a stable system. This is characterised by a dynamic equilibrium that propels a virtuous cycle, rather than a vicious one. Therefore, planners need to understand the whole system and its relationships, both internal and external. Centre of gravity analysis is good at unlocking the internal consistency of a friendly or adversarial system. But we can only conceptualise the whole system if we use centre of gravity analysis as part of the broader ‘equilibrium tool set’.

Equilibrium is a state of balance between opposing forces or actions.[13] It can be both static and dynamic. Equilibrium takes three forms – stable, neutral and unstable. If an object or system is in stable equilibrium it will return to equilibrium after a shock, this is a hallmark of resilient systems and people. Conversely, a system in unstable equilibrium can be tipped into chaos by a small force. The way U.S. Special Forces caused the Taliban collapse in 2001 is a good example. A system in neutral equilibrium remains so even if force is exerted against it. Consequently some systems are dynamic and still balanced. For instance, on the battlefield, a logistic chain that balances supply and demand is in neutral equilibrium despite supplies moving dynamically through the chain.

Economists, chemists, physicists, biologists and sociologists all use equilibrium theories to help determine optimum performance in their fields. In economics there are many equilibrium models.[14] They help economists manage and forecast macro-economic pressures, dynamic trends and market shocks. However, the complexity of economic models limits their practical field use. Military planners and practitioners need a simple set of tools that employ the logic of equilibrium theory without the intricacy of the economic models.

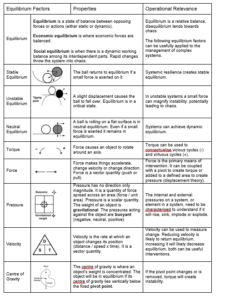

Potential tools include: pressure, velocity, force, torque and centre of gravity. Their physical properties and operational relevance are tabulated in Figure 1. The combination of these tools will help planners consider the relative balance of all factors and how they interact. For instance instead of just planning a line of operations, understanding internal and external ‘pressures’ helps the practitioner to work out if a system will rise, stabilise, sink, implode or explode. ‘Velocity’ can be used to measure, regulate and articulate the pace of change. ‘Force’ can indicate effort required to create effects. ‘Torque’ can be applied to create vicious or virtuous cycles, depending on whether a commander needs to destroy an enemy or build a society. Last but not least, centre of gravity is useful too as long as it is considered with another physics concept – the pivot point.

Physicists teach that an object will be in equilibrium if its centre of gravity lies vertically below a fixed pivot point. The centre of gravity and its pivot point are typically separate[15] (see Figure 1). That means if you alter a system’s pivot point it will oscillate and may need to find a new centre of gravity. The faster you do this the more volatile the result. To show how these tools can be employed, a hypothetical case study is offered.

Hypothetical Case Study

The Saudi Arabian centre of gravity may well be popular acceptance for the Saud Monarchy, as protectors of Sunni Islam. Yet, their centre of gravity is pivoted off global oil exports.[16] Significant internal pressure would be exerted on the Saudi system if; (1) global oil prices settled below economic levels, (2) a revolutionary technology replaced oil, or (3) Saudi Arabia lost sovereign control of their oil fields. For instance, if the Islamic State took over Saudi oil fields the loss of income would create destabilising oscillations (torque) throughout Saudi Arabia. This would be especially so if the scale and velocity of loss was rapid. Without sufficient external pressure to equalise the situation (such as increased revenue from another source) the monarchy’s legitimacy could be forfeit, thereby causing Saudi Arabia to explode into violence. The results of a Saudi breakdown would be far reaching; given Saudi Arabia is itself a pivot for Sunni Islam and regional equilibrium.

Ultimately centre of gravity analysis is a useful concept, but insufficient on its own. Military practitioners need to look to other fields for tools that forecast, manage and exploit the complex and adaptive nature of today’s security environment. Macroeconomics is one such field. Economists use a variety of tools to maintain dynamic market equilibrium. They do not always get it right: but if all they used was centre of gravity analysis they would almost always get it wrong. One reason is that centre of gravity theory has a one-eyed focus on the internal consistency of an object or system. The external environment and the relativity of forces need to be considered too – unless planners are hoping for multiple unintended consequences. Equilibrium theory offers new tools (pressure, velocity, force and torque) that can enhance centre of gravity analysis. More work is required to determine how these tools could be incorporated into military thinking. But suffice to say, it is time to rethink the way we visualise military operations.

[1] Carl von Clausewitz, Anatol Rapoport, ed., On War, (London, UK: Penguin Books, 1982), 389.

[2] Dr Joe Strange and Colonel Richard Iron, “Understanding Centers of Gravity and Critical Vulnerabilities,” http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usmc/cog2.pdf (accessed October 21, 2014).

[3] Boundless, “Center of Gravity,” linked from, https://www.boundless.com/physics/textbooks/boundless-physics-textbook/static-equilibrium-elasticity-and-torque-8/the-center-of-gravity-79/center-of-gravity-318-11272/ (accessed March 28, 2015)

[4] R. Craig Nation, “National Power,” in U.S. Army War College Guide to National Security Issues Volume I: Theory of War and Strategy 5th Ed, ed., J. Boone Bartholomees, Jr, (U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA: 2012), 155, http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=1109 (accessed January 29, 2015).

[5] Phillip Bobbitt, The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace and the Course of History, (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knof, 2002), xxii.

[6] Scott E. Page, Diversity and Complexity, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), 25.

[7] Ibid.,

[8] James Rickards, Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Crisis, New York, NY: Penguin Group, 2012), 201.

[9] Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable 2nd Ed., (New York, NY: Random House, 2010), xxi.

[10] Rickards, 211. For instance, it could be argued that the youth bulge in the Middle East increased chances for the current cycle of violence there.

[11] Rogernomics refers to the economic policies of Finance Minister Sir Roger Douglas. A free market ideologue, he embarked on an economic blitzkrieg, as he called it, to roll back the over regulation of the welfare state and open the New Zealand economy to the world. The irony is that Douglas was at that time a left wing politician. He later went on the found the most right wing party in New Zealand politics. Douglas was succeeded by Ruth Richardson as Finance Minister after the Labour (liberal) Government fell to the National Party (Conservative). Richardson was even more idealistic. Her opponents coined her economic policies ‘Ruthanasia.’

[12] Grant David, Bulls, Bears & Elephants: A history of the New Zealand Stock Exchange, (Wellington, NZ: Victoria University Press, 1997) 337, quoted in Stephen Keyes, “An Essay Revisiting Rogernomics in an Age of Globalisation,” June 19, 2012. https://unframednz.wordpress.com/2012/06/19/an-essay-revisiting-rogernomics-in-an-age-of-globalisation/ (accessed March 29, 2015).

[13] Bruce Moore Ed., The Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary, 3rd Ed., (Melbourne, Vic: Oxford University Press, 1997), 445.

[14] The dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model is used by the US Federal Reserve Bank and the European Central Bank, among others. Argia M. Sbordone, Andrea Tambalotti, Krishna Rao, and Kieran Walsh, “Policy Analysis Using DSGE Models: An Introduction,” Federal Reserve Bank New York Economic Policy Review, October, 2010, 23, http://app.ny.frb.org/research/epr/10v16n2/1010sbor.pdf (accessed March 28, 2015).

[15] The exception is when an object is symmetrical, in which case the centre of gravity may not change, even if the pivot point does.

[16] Saudi Arabia’s economy is largely based on oil revenue therefore it is a rentier State. A rentier State is a country that gets most or all of its income by renting or selling its natural resources to third parties.