Balancing Tradition and Change in the New Zealand Army

By Mr I. Brandon

Introduction

Tradition plays a positive role in any Army, by helping to strengthen the moral component of its fighting power. The strong moral fabric and esprit-de-corps that we strive to cultivate today in the New Zealand Army is firmly anchored in our past. Preserving our historical understanding helps to build collective pride, confidence and a sense of purpose. It keeps us grounded and connected to our military whakapapa – while also inspiring us to live up to the expectations of those who have gone before us. There are sound reasons why the distinguished traditions of Ngāti Tūmatauenga should be carefully cultivated and curated.

Tradition manifests itself in a number of ways within the Army, including how we think about our force structures and operating model. In these areas, it carries potential downsides. It can limit innovation, unduly influence how we operate and create cultural barriers that prevent a military from adapting to meet the challenges of an ever-evolving world. First and foremost, an Army must remain credible, capable, relevant and responsive to the current environment to be of continued utility to its Nation.

As growing regional competition, climate change, economic challenges and a host of other emergent threats begin to impact New Zealand, it is timely to ask whether our Army continues to strike the right balance between tradition and adaptation concerning our force structures and operating model. I contend that to remain capable and ready to meet the challenges facing New Zealand now and into the future, it is necessary to consider some changes to our approach in these areas while preserving the benefits that other aspects of our traditions still generate.

In this article I will lay out an argument for why our outputs require greater strategic definition to drive force structures and force generation processes, and the powerful impact this work would have on organisational unity of effort. I will outline suggested changes to our force structures and operating model for our manoeuvre units and combat trades, which will led to greater efficiencies in force generation and operational effectiveness. Lastly, I will touch on how we could adapt our approach to output management to mitigate the risks associated with some of these changes.

Incremental Improvement versus Transformation

Our Army has been on a journey of continual change for at least 20 years – beginning when New Zealand was forced to contend with the spectres of regional instability and global terrorism. During my time in the service, we have seen the introduction of world-class weapons, soldier systems and vehicles. We have improved our training systems and have also now embarked on an important process of digitisation through the Network Enabled Army Programme.

These changes have, however focused more on incremental improvements and upgrades to capabilities rather than changing the structures and processes within which they are employed. Organisational norms concerning regimental structures and trades have been largely retained by deliberate decision or through unconscious bias, and attempts at implementing change that have run against these traditions have tended to fail due to institutional inertia if not outright resistance. We have, therefore, missed opportunities for genuine transformation as exciting new capabilities have been introduced into service in recent years.

The Power of Why: Strategic Definition of Outputs

There are other barriers to organisational change and the necessary unity of effort to see it through. For many years now, our Army has operated without a clear, shared understanding of our outputs or operating model to the necessary level of fidelity. Army strategy has tended to focus on conceptual objectives at greater range, without defining what the Army must deliver in the here and now. The capability definition documents produced by NZDF Capability Branch do not quite fill this gap.[1] Change initiatives that have not been anchored by clear strategy have tended to fail in the long-term due to a lack of organisational alignment, as well as the buy-in that generates the infrastructure, human resourcing, funding and necessary determination to ensure success.

One method of addressing this problem would be the development of strategic definition documents, authored by Army General Staff, which describe our combined-arms platforms holistically and in detail. These documents could describe orders of battle and capabilities as well as explaining how the platform will achieve its directed outputs within different employment contexts and to specific conditions and standards. They would align with the NZDF Output Plan, would complement the Army Plan and would inform the Army Operating System – providing a clear picture at the strategic level of the tools the Army will employ to accomplish all of its integrated land missions. Our primary conventional platform, and the focus of this article, is the Motorised Infantry Battle Group (MIBG).[2]

The power and impact of such an artefact would be immediately apparent. It would help to inform and better align our planning relating to force structures and force generation at all levels (which should logically link to our platform and its outputs). It would assist NZDF Capability Branch to meet the current and future capability needs of the MIBG by clearly articulating and placing in proper context the broad user requirements of our platform. It would also serve as a solid reference for the Army when developing business case bids to secure funding and resources.

The Capstone Orders work that has been initiated within Army General Staff with the publishing of the Army Command Statement 2022 is a very good start point.[3] As explained by Simon Sinek, articulating the ‘why’ that underpins any organisation’s reason for being in a manner that can be clearly understood is a catalyst to developing a strong sense of shared purpose, vision and commitment.[4] Similarly, clear alignment with Australian Defence Force doctrine and capabilities will help to ensure that New Zealand can offer its MIBG as an interchangeable or at least interoperable contribution to an Australian Army Brigade within an ABCANZ Divisional construct.

To progress this important strategic work, the right quality and quantity of human resources are required. To this end, the Army should continue to encourage and prioritise more of our best and brightest Officers and Warrant Officers for postings to Army General Staff. Our regeneration following Op PROTECT provides the perfect opportunity to transform our way of thinking and operating, and Army General Staff must be the engine room to drive this change within the Army by way of robust and detailed strategy. The benefits of cultivating a strong Strategic Centre would manifest themselves for many years ahead.[5]

Manoeuvre, Reconnaissance and Strike

The Army currently constitutes three manoeuvre units plus separate enabling units to deliver its directed range of capability bricks and outputs at a roughly 3:1 force generation cycle. This approach has proven to be increasingly challenging to sustain in recent years due to a combination of personnel recruiting and retention challenges as well as operating budget, infrastructure and equipment limitations.

The imminent introduction of PMV-M could further exacerbate this issue. It will create even greater pressure on our units to do more with similar levels of personnel, infrastructure support and operating budget, and further dilute the specificity of training needed to generate a genuine combined arms battle group at a credible level of readiness. The temptation exists to shoe-horn the PMV-M into service using existing structures and operating models, rather than treating it as an opportunity for transformational change. This will degrade our ability to build truly integrated, organic motorised infantry sub-units and risks propagating a mindset that our primary combat and protected mobility vehicles are simply transport assets rather than combat-multiplier capabilities in their own right.

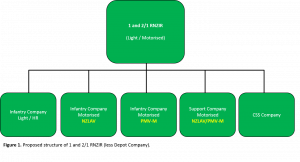

To establish a more sustainable and effective approach, I propose that the Army instead adopts a 2:1 force generation model based on 1 and 2/1 RNZIR as the basis of our deployable MIBG. The lead unit for meeting and maintaining Directed Level of Capability requirements could be rotated every 12-24 months depending on what was assessed to be the optimal length for a force generation cycle. Noting our current procurement decisions for PMV-M, each battalion could deliver light infantry (including high readiness) as well as motorised infantry effects at the company level once personnel numbers allow. Complete integration of vehicles with the infantry they are designed to support will enable the Army to fully leverage the capabilities of these platforms and build the type of instinctual relationships required between soldier and vehicle platform for maximum combat effectiveness.

With sufficient personnel, each battalion could eventually contain a light infantry company, a company organically mounted in NZLAV, and a company organically mounted in PMV-M. This would provide the Government and ultimately the MIBG commander with a range of capabilities to choose from to task-organise and achieve desired effects within different environments and mission profiles.

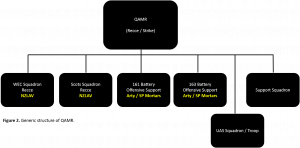

Queen Alexandra’s Mounted Rifles would assume an important but different role under this proposal. It would move away from generating motorised infantry effects, and instead adapt to fulfill a very specific function: generating reconnaissance and strike capabilities, including deep(er) fires, to integrate into the MIBG at sub-unit level.

Cavalry of old were designed to conduct recce and screening missions, as well as being capable of achieving decisive effects on the battlefield if the right conditions were encountered. Recce squadrons could become our modern version of cavalry, with NZLAV-mounted soldiers who are trained specifically to conduct mounted and dismounted reconnaissance, as well as bring additional firepower to a fight as needed. Two recce squadrons, operating under a 2:1 force generation cycle, would be sufficient to provide a deployed MIBG with the operational effects it requires.

The recent experiences of others in preparing for and prosecuting operations against a near-peer opponent suggest a combat advantage can be gained by creating closely integrated relationships between ISR and strike capabilities where the passage of targeting intelligence and response times can be streamlined. The Russian Armed Forces have worked to develop this capability through their concept of the reconnaissance fires complex. The Ukrainians, with significant support from partners, have linked ISR capabilities to responsive fires in a way that has assisted them to achieve significant tactical successes against their more powerful adversary. And the UK has commenced a similar development journey through the recent creation of the 1st Deep Recce Strike Brigade Combat Team.

To achieve similar benefits appropriate to the scale of our MIBG output, our Army could consider subsuming the offensive support capabilities provided by 16 Field Regiment into QAMR. Two offensive support batteries would operate alongside the recce squadrons contained within the Regiment. As the 105mm Light Gun is phased out, the Army could seek to replace it with something with sufficient mobility and firepower to support motorised combat operations such as a self-propelled mortar system. The batteries would, not surprisingly, also operate under a 2:1 force generation cycle. Joint Fire Teams would remain an important capability, and would organically integrate with reconnaissance elements to create a credible recce strike capability as new offensive support weapon systems are introduced. Challenges concerning offensive support training or governance aspects at unit level could be mitigated through having an appropriate fires training cell and other supporting staff officers embedded within HQ QAMR or Brigade HQ. It follows that QAMR in its updated form could be commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel drawn from the RNZA or RNZAC.[6]

QAMR would also contain another very important capability: UAS. We urgently need to drag these systems out of the battle lab and into service via a formal capability project. The world is rapidly adapting to the opportunities and impacts of UAS on the battlefield, as vividly but not exclusively illustrated by current operations in the Ukraine. Our MIBG must not be left behind, and these systems would form a critical component of a future recce strike capability.

Army Combat Trades: Effects not Platform Focused

So what about the trades? The Army will still need the knowledge and skills provided by infantry, armoured and gunner combat specialists. However, our Army could adopt a more flexible approach to individual training models to create truly integrated systems within units. For example, all NZLAV and PMV-M within our infantry battalions could be operated by RNZIR personnel. This would mean that we would need to invest significantly more time in training at least a proportion of our commanders to operate in both mounted and dismounted roles.[7] It follows that armoured combat specialists would train to operate the NZLAV within QAMR, but would also become skilled at all aspects of mounted recce, dismounted recce and the provision of fire support using vehicle weapon systems. Perhaps a better title for the trade would be armoured reconnaissance specialists. The bottom line is that our combat trades could become more aligned with effects rather than specific platforms. This could well lead to richer and more diverse career development opportunities for our junior soldiers in those trades.

Output Management

A 2:1 force generation cycle demands a disciplined approach to allocating forces to operations. Any force elements committed piecemeal from the MIBG ORBAT to service smaller deployments should be struck off rather than being sourced ad hoc from other parts of the Army. This will ensure that our operating model remains sustainable over the longer term by preserving those other components of the Army dedicated to delivering training, providing enabling capabilities, meeting other outputs (including HADR), managing change and tackling the myriad of other organisational overheads.

The obvious question regarding a 2:1 force generation cycle is how MIBG operational deployments would be sustained for the duration expected by the Government. While detailed discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this article, a range of options could be considered. Standard deployment lengths could be extended to eight, nine or even 12 months for larger Task Groups if necessary to create sufficient time for the force generation of subsequent rotations. Lengthening the time between rotations would also create additional scope for the Army Reserve to augment or replace force elements. It is a fine aspiration for our Army to continue to pursue the full integration of our Army Reserve into our operational sustainability planning, and this will serve as a catalyst for their own transformational changes to occur.

Conclusion

The ideas laid out in this article are not particularly revolutionary. They suggest tweaks to traditional thinking about our operating model and trades, rather than advocating wholesale change. Our Regimental systems still create benefits for the Army in terms of how it manages and sustains its people, equipment and capabilities. We should seek to preserve what works to enable all components of our fighting power, while remaining flexible in areas where focused change can create positive long-term impacts.

I have neglected to discuss the possibilities and opportunities for the other enabling units and capabilities that support the MIBG, or deliver other outputs such as HADR. Further work is also required to consider Army Reserve forces as well as the impacts on our training organisations. These are good topics for further discourse.

This article is intended to generate robust conversation, constructive criticism and new ideas for consideration. My challenge to serving personnel is that if you do critique these ideas, then present some alternative ones instead. If you think you have something to offer that could inform our Army’s strategic direction over the next five to ten years then write about it. And if you are truly passionate about these issues, then get yourself posted to Army General Staff where you can be part of generating the solutions to our multitude of organisational challenges. These challenges are shared by all those who serve in our Army, and we should therefore all strive to be involved in developing and implementing the steps to generate meaningful and necessary change.

Footnotes

[1] Capability definition work at the highest level focuses on component warfighting functions rather than defining our combined-arms platforms through an outputs lens. And attempts to complete this high-level definition work over the past ten years have achieved mixed success. The Army is responsible for the MIBG output, and therefore work within NZDF Capability Branch in support of it should be derived from Army strategic direction.

[2] Other conventional Army outputs that would also benefit from greater strategic definition are the HADR Task Group, and enablers to other Joint effects.

[3] Refer to the Army Command Statement 2022, which is the first of the published Capstone orders. An Army Plan and Army Operating System will likely follow.

[4] Simon Sinek, Start With Why (Harlow, England: Penguin Books, 2011).

[5] The Army could also be more explicit about linking higher education and specific overseas postings to follow-on employment in Army General Staff. This will ensure a steady flow of the latest ideas and experiences from our partners abroad.

[6] The UK 1st Deep Recce Strike Brigade Combat Team consists of armoured recce as well as close support and deep fires artillery units. Its first commander was a Brigadier drawn from the Royal Artillery.

[7] Similar to what was previously attempted with the ‘cavalry’ concepts within 1 RNZIR and QAMR. The use of the word cavalry in that context was, however, a misnomer. From an effects perspective they were motorised infantry.